Leber congenital amaurosis (LCA)

Leber congenital amaurosis (LCA) refers to a group of diseases that cause severe vision loss in infancy. The vision loss is due to abnormal function and later degen-eration of the retina, the layer in the back of the eye that captures images, similar to the film in a camera. With LCA, the light-sensing (photoreceptor) cells of the retina do not function properly, causing an inability to capture images.

LCA

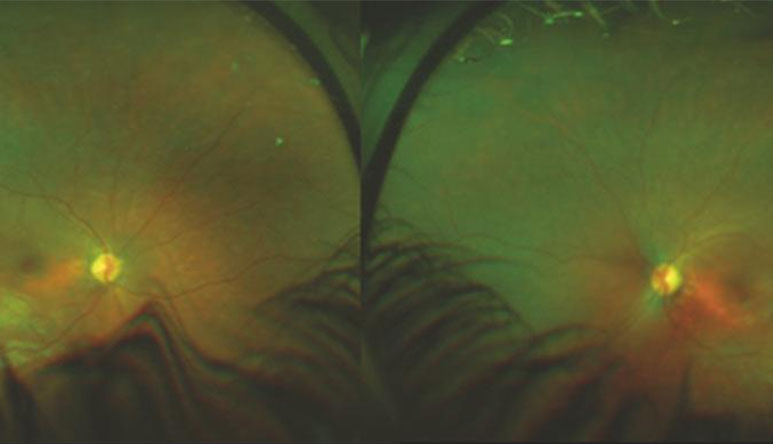

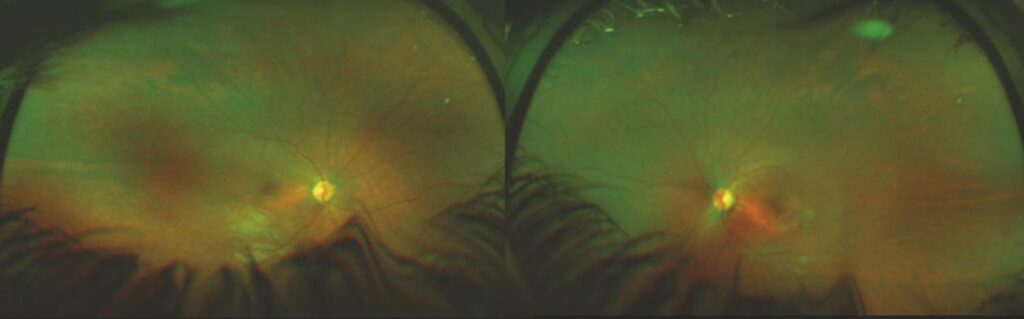

Figure 1:

Widefield fundus image of 9-year-old child with Lebers Congenital Amaurosis (Audina Berrocal, MD, University of Miami, Bascom Palmer Eye Institute.)

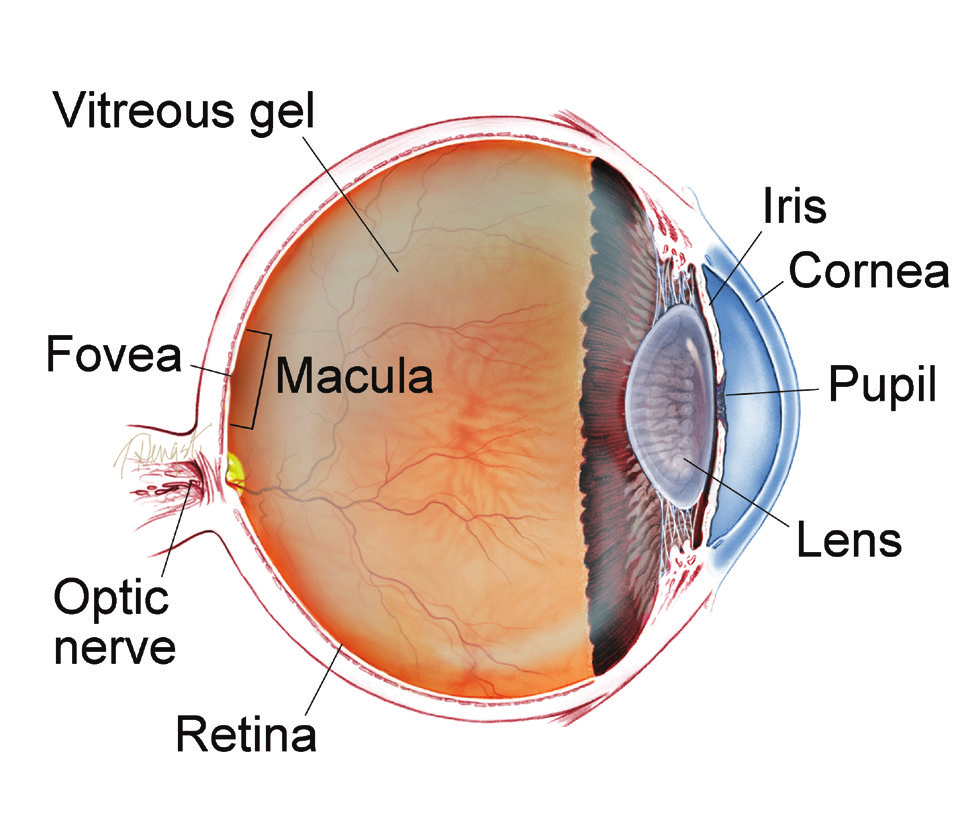

WHAT IS THE RETINA?

THE RETINA is a thin layer of light-sensitive nerve tissue that lines the back of the eye (or vitreous) cavity. When light enters the eye, it passes through the iris to the retina where images are focused and converted to electrical impulses that are carried by the optic nerve to the brain resulting in sight.

Causes and Risk Factors:

Leber congenital amaurosis LCA is inherited (passed down from parents) through their genes. There are at least 19 different gene mutations that can be passed down and cause the spectrum of LCA. The affected genes instruct our body to make proteins that are necessary for vision.

In Leber congenital amaurosis LCA, the abnormal genes are typically passed down in an autosomal recessive pattern. This means that in order to have the disease, the child needs two abnormal genes, one from each parent. Both parents are typically unaware they carry the mutation, as they do not have vision loss.

Diagnosis and Testing:

On ophthalmic examination, patients with LCA often initially have a relatively normal-looking retina, as the degeneration of the retina occurs later. The diagnosis can be confirmed with an electroretinogram (ERG), which measures the activity of the retina. LCA patients classically have a “flat” ERG, which suggests virtually no retinal function. Later, the retinas become damaged and show thinning, often with pigmentary changes, and the optic nerve heads become pale.

Genetic testing is important to determine which gene is abnormal. Genetic counseling can also help parents and patients understand the inheritance and the risk of future children having the condition. Some mutations cause problems in other organs of the body, including developmental delay, so it is important for affected children to be evaluated by a pediatrician experienced in treating inherited diseases.

SYMPTOMS

LCA is usually detected in children when they exhibit profound visual impairment, although the genetic abnormality is present from birth.

Parents may notice their child does not seem to fix his or her gaze on objects or follow moving objects. This visual impairment is often accompanied by eye rubbing, as the rubbing stimulates the photo receptor cells to see light.

Some forms of LCA may not affect visual function until months or years after birth. One form, caused by two abnormal RPE65 genes, usually affects night vision first (vision in a dimly lit room). Later, vision is affected under all lighting conditions and eventually all vision is lost without treatment.

Treatment and Prognosis:

Although LCA typically leads to progressive loss of all vision, new advances in gene therapy offer hope for some patients. This new therapy involves implanting new genes into the abnormal retinal cells to correct the defective gene.

Recently, gene therapy has become available for patients with mutations in both copies of the RPE65 gene. A defect in this gene can cause LCA in some patients as well as retinitis pigmentosa (RP) in others. RP is a disease similar to LCA that occurs later in life.

Voretigene neparvovec-rzyl (Luxturna™) is the gene therapy product injected underneath the retina, allowing a new, functional copy of the gene to pass into the appropriate cells. It is the first gene therapy approved by the US

Food and Drug Administration (FDA) to treat a disease. Luxturna™ requires a common retina surgery procedure called a vitrectomy, and must be done by an ophthalmologist with experience in injecting genes under the retina.

This treatment has been shown to improve vision in patients who have received it, as tested by their ability to navigate an obstacle course in low light conditions termed “multi-luminance mobility testing” (MLMT). While Luxturna™ does not completely restore vision, the improvement noted in clinical trials can be beneficial for patients with extreme vision loss. The visual improvement is stable over at least a few years.

Because this therapy is so new, many patients who are eligible for the treatment do not know about it. The FDA has approved Luxturna™ for patients 1 year of age or older. The most important first step is obtaining a diagnosis of LCA or RP, and then performing genetic testing to determine if there is a defect in both RPE65 genes.

Patients must also have enough remaining functional retina so treatment can stabilize or restore vision. Because younger patients may benefit more from the treatment, it is important for these children to be diagnosed as early as possible.

Once the diagnosis is made, a retina specialist who is an expert in inherited retinal diseases can refer the patient to a treatment center. Eventually, through further research, it is expected that gene therapy could help individuals with other gene mutations.

Other LCA treatments involve artificial implants to bypass the non-functioning photoreceptor cells. A more detailed explanation of these implants can be found by visiting the Retinal Health Series portal (www.asrs.org/retinahealthseries) and clicking on the Retinitis Pigmentosa and Retinal Prosthesis tab. Finally, low-vision specialists can work with patients to use tools and technology to improve quality of life and functioning.

Electroretinogram (ERG): Non-invasive test that measures the electrical “circuitry” of the eye by assessing the response of the retina’s light-sensitive cells to stimulus.

Retinitis pigmentosa (RP): A group of inherited (passed down from parents) diseases causing retinal degeneration and blindness. Individuals with RP lose their vision because photoreceptor (light-sensing) cells of the retina gradually degenerate and then die

Bibliography

THANK YOU TO THE AUTHORS

Sophie J. Bakri, MD Audina Berrocal, MD

Thomas Ciulla, MD, MBA Geoffrey G. Emerson, MD, PhD Roger A. Goldberg, MD, MBA Dilraj Grewal, MD

Larry Halperin, MD Vi S. Hau, MD, PhD

G. Baker Hubbard, MD Talia R. Kaden, MD

M. Ali Khan, MD

Mathew J. MacCumber, MD, PhD Timothy G. Murray, MD, MBA Oded Ohana, MD, MBA Jonathan L. Prenner, MD

Carl D. Regillo, MD, FACS Naryan Sabherwal, MD Sherveen Salek, MD Andrew P. Schachat, MD Michael Seider, MD

Janet S. Sunness, MD Edward Uchiyama, MD Allen Z. Verne, MD Christina Y. Weng, MD, MBA Yoshihiro Yonekawa, MD

EDIT OR

John T. Thompson, MD

MEDICAL ILL US TRAT OR

Tim Hengst

Copyright © The Foundation American Society of Retina Specialists

Committed to improving the quality of life of all people with retinal disease.